It was a sad day for me when Marks & Spencer in the city centre announced it would be closing. It was a loss to my neighbourhood.

Broadmead was the first place I visited in Bristol when I moved here to start a PhD. I was staying at the hotel at the Haymarket so I popped over to the Galleries across the road for a jacket potato at the food court.

I’ve lived within less than a mile of it ever since. My food shopping relies on what’s available. Travel, schooling, and health are all determined by what’s within walking distance.

This is very much my neighbourhood that is changing so, when I write about it, I’m writing about something that directly affects me but which I, and thousands of other residents, have no power to influence.

Change is being orchestrated around us, and it has a name and it has a purpose.

Who benefits?

The answer to that comes with understanding that “gentrification, both as a term and process, has always been about how housing opportunities of middle-class people are expanded while those of working-class people are restricted” (Slater, 2021).

In Shaking Up the City, Slater points out we need to be asking “who and what makes urban land profitable for (re)development” and “urbanization for whom, against whom, and who decides?”

For Whom?

In October 2021, the mayor graced us with a weary but accepting tone when asked about the closure of one of the few wide-ranging food providers in the city centre (only 2.6% of retail floorspace is dedicated to main food shopping there).

“I’m sad to see Marks and Spencer decide to leave Broadmead and end almost seventy years of association with the city centre,” he told Bristol Live.

“Whilst this closure is a blow to our already struggling high streets, it is not a surprise.”

No, it’s not a surprise. When the Debenham’s closure was announced earlier this year, the mayor’s blog post about future plans for the area bordered on ecstatic: “as the site freeholder, this gives the council a once in a lifetime opportunity to redefine how it can productively play a role in the future of Bristol’s city centre.”

We residents were losing something but the council and their partners seemed happy.

“Castle Park View site will provide 375 new homes,” he boasted. I imagine he was eager to work towards the mayoral target of building 2,000 new homes each year by 2024 that has to be met.

According to the mayor, the council has a chance to develop the area. They can pursue housing, leisure and “new and alternative day and night-time uses”.

More leisure might help bring in more “branded cafes and coffee shops at Broadmead / Cabot Circus,” according to a retail review published by the council in 2014. “Despite the area’s food and drink offer,” it “lacks an evening economy focus and is not supplemented by a sufficient critical mass of entertainment, leisure and community facilities” (link).

For who?

These directions for the city centre aren’t new. The June 2020 city centre framework supported “the development of new homes and workspaces as we regenerate the centre, alongside diverse and vibrant uses to create a thriving daytime and night time economy.”

The night-time economy element is supported not only by a new Bristol @ night board but also a night-time economy czar. The new gain by the live music industry, the ‘agent of change’ principle, places the burden of reducing disturbances to developers who build new housing. This also helps the night-time economy.

Further plans for regeneration will be announced in spring 2022, with the publication of the City Centre Development and Delivery Plan (DDP), which “will define [the council’s] place-making principles for the city centre” [Mayor’s blog].

However, note that word: place-making. Let’s pause there for a second, and not just accept the term and the implications that it is positive.

As Tom Slater (2021) writes about placemaking, “There are uncomfortable parallels with colonialism: in any context where placemaking is planned, what if there is a place already there, one to which residents might be deeply attached and might not want transformed?”

What changes have we seen?

In 2014, a retail review study of Bristol city centre, found that it was ranked 12th in the national Venuescore of retailers. It had “30 of the top 31 major retailers, the vast majority of which – including Debenhams, House of Fraser and Marks & Spencer – are focused within the prime retail area of Broadmead/ Cabot Circus.”

At that time, the aspirations for the expansion of The Mall at Cribbs Causeway were the biggest threat for Bristol’s retail space at the time.

In 2021, with a new Labour administration, post-Brexit, in a pandemic, the city centre still includes Primark’s regional flagship store but a few of the big names have gone. The Galleries was sold in 2019 for £32m, £18m less than it had been bought for in 2011. Despite the millions spent by InfraRed on making the Galleries “lighter, brighter and more modern” they could not compete with Cabot Circus and the changes in the area.

A clue that Bristol City Council were prioritising Cabot Circus over Broadmead was that the former’s car park is excluded from the upcoming Clean Air Zone, but seemingly not so the Galleries’ one.

There is a sense that our city centre’s future had been decided long before October 2021.

The authors of the framework go on to say:

This framework reflects our ambitions to strengthen that ranking* by further regenerating Broadmead to include more leisure and experience opportunities both day and at night, supporting and promoting the independent offer, and bringing in new homes, workspace and better quality spaces.

By ‘that ranking’ they mean being 12th (in 2014 and 2017). As we saw, that was granted when the city centre had major retailers. It has lost quite a few of them now though.

Leisure opportunities might be a reference to places such as a potential bowling alley opening opposite the Galleries. But what could ‘better quality spaces’ refer to?

In the framework and in the blog post, we have some clues as to ‘for whom?’ these changes are being made and ‘by whom?’

The City Centre Revitalisation Group includes key stakeholders with an interest in the economic vitality and future of an inclusive and vibrant city centre – Destination Bristol (responsible for the City Centre and Broadmead Business Improvement Districts), Business West, University of Bristol, Bristol Hoteliers Association, property owners and developers, Royal Institute of British Architects, Bristol@Night panel, representatives from the creative sector, and Bristol City Council.

To look at just one of the partners listed above, Business West is the chamber of commerce for the area. This month the CEO of YTL-owned Wessex Water, Colin Skellett, joined them as a director.

YTL were the ones who offered hospitality to Bristol mayor Marvin Rees, and who later went on to receive planning permission for an arena in Filton. More information on that can be found here but it’s worth noting that the University of Bristol benefited from the sale of land at Temple Island too. It’s where they are setting up their new campus.

The council’s decision to change the arena’s location was predicted at the time as the death knell to Broadmead. Building the arena at Filton would compound the effect of expanding the city centre’s competitor, the Mall at Cribbs Causeway. The threat was seen in the strengthening of “the retail and food and beverage offerings surrounding the Filton site. With 39% and 33% of the average spend of a day visitor in Bristol consisting of shopping and food and drink respectively, these two spending areas, collectively make up more than two thirds of the total average expenditure for a day visitor in Bristol” (see Assessment of Alternative Plans for an Arena in Bristol.

The redevelopment of the city centre has been designed to progress in the manner we are seeing. Residents lose out and developers write the strategic frameworks for how change happens. The administration gets its housing, YTL get funding for infrastructure (and an arena if they choose to build one), and the University of Bristol get their new campus and 3000 more students.

Against whom?

Communities

To look at who these changes are against, one clue is the closure of M&S, which had one of the food courts in Broadmead and Cabot Circus. The biggest supermarket in the city centre is the Tesco Metro at Broadmead. It’s only big compared to the little dinky shops that litter seemingly every street. More of these have opened up but they hardly add much to the choice for family shopping. Their focus is mostly on the office workers, shoppers, students, and casual passers by. Our closest one has three times the shelf space for sandwiches & meal deals than it does for ingredients for cooking, such as pasta, rice, El Paso kits, olives, etc.

In the ever-expanding city centre, with a goal of bringing in thousands more residents, we are seeing the emergence of ‘food deserts.’ These are “disadvantaged areas of cities with relatively poor access to healthy and affordable food”. The bigger supermarkets are further out in the suburbs or more residential areas while “residents of inner-city neighbourhoods of low socioeconomic status have the poorest access to supermarkets”. Cabot Circus has leisure space and restaurants but no food shopping.

An emphasis on the night-time economy and aspirations to a New-York-like city that never sleeps doesn’t sound appealing for residents with families.

Rough sleepers

My demographic is not the only one affected, of course, and others face much serious consequences with fewer or no choices.

The Galleries and Broadmead used to feel safe but this is no longer true. National changes have included immense cuts to local funding, which has led to a tenfold (and more) increase in homeless people in Bristol. The city has the second highest number in the country. At Broadmead, the rise in police incidents shows how people become criminalised because of activities that others can do in bars or at home, including drinking and sleeping.

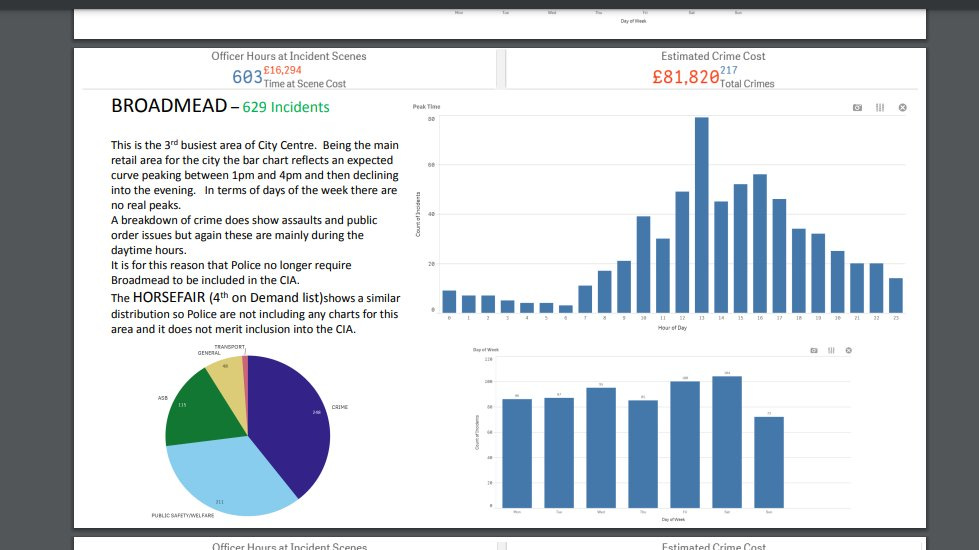

We know that there are quite a few incidents involving the police in Broadmead.

Data from Avon and Somerset Constabulary show that Broadmead is the third busiest area in terms of police presence. However, unlike with other central areas, most incidents — including assaults and public order issues — occur between 1pm and 4pm in the afternoon. This isn’t an effect of the night time economy. It’s a cluster of people who have nowhere else to go.

Rough sleepers don’t just camp out in the city centre, of course, but the rise in numbers has been visible, and central locations mean people are closer to services. The plans for Broadmead don’t seem to be heading in the direction of housing rough sleepers so what happens to these people?

The council decision to partner with Caridon and house people at Imperial Apartments, at a distance from the centre, is one example of how rough sleepers are treated.

Caridon have been called ‘The millionaire businessmen behind tiny slums of the future’. Their “flats are among the smallest in the country, with some measuring 14 square metres (150sq ft).

The group director, Mario Carrozzo’s sprawling Surrey mansion, in contrast, includes a tennis court, indoor swimming pool and cinema.

“The £6 million home has three sitting rooms, a gym, spa and games room with bar. It is a far cry from the tiny flats his property empire is built on.” [link]

The council saves money by having dedicated accommodation for homeless people because it’s the government that pays housing allowance from tenants to Caridon. The group “are reported to have received over £8 million in housing benefit for putting people up in these conditions.” [link]

In Bristol, the “total gross annual rent to Caridon for the 266 units will be approximately £1.9m” [link] and rent is guaranteed by the council.

Concerns include the development “being high density and the flats not meet[ing] planning space standards,” not being “suitable for wheelchair users” and, according to the equalities impact assessment, “the majority of families moving in to the development are single parent (mainly female) families with a small child/children.”

“Young women may feel anxious, unsafe or isolated. Single males may feel bored.” There is no aspirational enthusiasm with this housing, and no ‘once in a lifetime opportunity’ for the council.

One might, I think reasonably, ask whether issues with rough sleepers from the city centre are being transferred out of eyesight.

The mayor’s blog post is called “A city centre for everyone, day and night” but as we’ve seen, that doesn’t include residents and it is doubtful if it includes rough sleepers.

We’ve gone from an administration where the expansion of the Mall at Cribbs Causeway was seen as a major threat to one that seems actively trying to help Cribbs grow.

As we watch the upcoming changes, we need to keep in mind: “for whom, against whom, and who decides?”

Hi Joanna, Really interesting piece. No mention however of the changes in shopping habits nationally. City centres are being reimagined all over the place because needs must. I do understand the need for local services for local residents and the homeless community but it's a balancing act surely.